Amy Austin Renshaw

Marshall van Alstyne

One school of change management argues that old practices must be "obliterated" and new processes designed from scratch to fully leverage new technologies and business realities. In practice, few managers have the luxury of re-designing their processes or organizations from "clean sheet of paper" - people, equipment and business knowledge cannot be so easily scrapped. Furthermore, organizational change almost inevitability becomes a learning process in which unanticipated obstacles and opportunities emerge (Orlikowski & Hofman, 1996). Recognizing this, movements like Total Quality Management have sought to institutionalize continuous learning and incremental improvement. This approach has been formalized and greatly aided by tools like statistical process control and the "House of Quality" (Hauser & Clausing). However, some types of organizational change are riskier if undertaken piecemeal or incrementally. Existing tools are often inadequate when radical change is contemplated (Davenport & Stoddard). To make matters worse, when the costs of change are considered, it may not even be clear whether the best course is to strive for radical change, incremental change or no change at all, even if a potential organizational goal is precisely envisioned and represents an unambiguous improvement.

The difficulties many organizations have had with change management depends in large part on an inadequate recognition of interdependencies among technology, practice, and strategy. However beneficial a new machine, incentive system, product line, decision-making structure or reporting system may appear in isolation, the acid test is how it interacts - as it must - with numerous other aspects of the organization. Recognizing the critical role that interdependencies play in affecting outcomes leads to new analysis and theory (Crowston & Malone; Barua, Lee & Whinston). For instance, Milgrom and Roberts show mathematically how interactions can sometimes make it impossible to successfully implement a new, complex system in a decentralized, uncoordinated fashion. Instead, managers must plan a strategy that takes into account and coordinates the interactions among all the components of a business system. In other cases, interactions can create a virtuous cycle of positive feed back which amplify even small steps in the right direction. Because new organizational paradigms eliminate time, space, and inventory buffers as operations become more tightly coupled, ignoring such interdependencies is becoming increasingly risky (Rockart and Short).

In this paper, we introduce a new tool, the Matrix of Change, which can help managers anticipate the complex interrelationships surrounding change. Specifically, the tool contributes to understanding issues of feasibility (stability of new changes), sequence (which practices to change first), location (greenfield or brownfield sites), pace (fast or slow), and stakeholder interests (sources of value added). The Matrix of Change was inspired by formal analyses of Milgrom and Roberts while it draws also upon established design principles of Hauser and Clausing. Implementation steps may already be familiar to anyone acquainted with qualify function deployment (QFD) or the House of Quality. The resulting support for process design, analogous to product design, becomes formal and systematic but remains managerially relevant and intuitively accessible.

An old proverb states that "you can't cross a chasm in two steps." The same wisdom applies to many organizational change efforts. Advances in information technology (IT) and rising competition have led to new modes of organizing work. Many of these new organizational forms depart from past practice instead of incrementally improving it. The resulting gains for companies can be substantial. Hallmark, for instance, discarded sequential product development in favor of cross-functional teams and reportedly reduced new product introduction time on one card by 75%. After reorganizing, Bell Atlantic cut service order rework and saved $1 million annually, while simultaneously improving product quality (Hammer and Champy).

Frequently, however, business process reengineering efforts run into serious difficulties. By some estimates, 70% of such projects fail to reach their intended goals (Bashein, Markus and Riley; Hammer and Champy), and a program that seeks to become a "House of Quality" more often becomes a "House of Cards." Because success often depends on coordinating the right technology, the right product mix, and dozens of the right strategic and structural issues all at the same time, near misses can leave a firm worse off than if the change had never been attempted. While several studies have documented the importance of coordination (Jaikumar; Krafcik and MacDuffie; Parthasarthy and Sethi), managers continue to have difficulty achieving it. Often, the problem is not that the proposed system is unworkable but that the transition proves more difficult than people had anticipated (Champy). Too often, managers proceed in a hit-or-miss fashion, implementing the most visible bits and pieces of a complex new system, unaware of hidden but critical interconnections.

The path to change has several stumbling blocks. Some companies cannot adapt or they miss new opportunities, leaving them vulnerable to startups (Henderson and Clark). Sometimes companies acquire technology without modifying their human resource practices, mistakenly assuming "technological determinism" _ that technology's effects are independent of the organizational structure in which it is embedded. In the 1980s, for example, General Motors spent roughly $650 million on technology at one plant without updating its labor management practices. As it turned out, the technology upgrade provided no significant productivity or quality improvements (Osterman). Likewise, as Jaikumar found, US companies adopting flexible technology often fail to achieve the same gains as comparable Japanese businesses because they do not alter related operating procedures. Recently, Suarez, Cusumano and Fine found that the most flexible plants in their sample of printed circuit board manufacturers were those with the right combination of human resource practices, supplier relations, and product design - not necessarily those with the most advanced technology. Econometric research also suggests that while IT investments are often associated with higher productivity, complementary organizational changes are at least as important (Brynjolfsson and Hitt).

The Matrix of Change presents a way to capture connections between practices. It graphically displays both reinforcing and interfering organizational processes. Armed with this knowledge, a change agent can use intuitive principles to seek points of leverage and design a smoother transition. Once the broad outlines of the new system and the transition path have been charted, authority can more effectively be decentralized for local implementation and optimization.

The Matrix highlights interactions and complementary practices. An example of a collection of critical complements includes the use of flexible machinery, short production runs, and low inventories (Dudley and Lasserre; Milgrom and Roberts). Emphasizing one such practice increases returns to its complementary practices. Likewise, doing less of a given complement reduces returns to its operating dependents. In this example, more flexible machinery draws value from and adds value to shorter production runs. Trouble starts when change agents fail to identify feedback systems that push business units back toward old ways of doing business or when they miss synergy that would strengthen the new and better ways they wish to establish.

Ironically, the bottom-up, continuous improvement principles associated with TQM can also be counterproductive - it may be that no single isolated change can improve a process, but a coordinated change can. Incremental change can sometimes be more painful than radical change. Twenty-five years ago, the Swedish government decided to shift from driving on the left side of the road to driving on the right. The scope of the change was enormous. When faced with dramatic change, affected parties often plead for time to adapt. But, imagine the consequences of asking the trucks to drive on the right-hand side during the first month of the transition and then the cars in the second month! Some transitions are smoothest when everyone changes their behavior quickly and at once. Although empowerment and decentralized decisions are popular, this practice can certainly fail if uncoordinated - imagine each driver independently determining the best side of the road for driving. As it turns out, Sweden made the change quickly during the least trafficked hours of night. Once the plan was universally communicated, it was in each individual driver's best interests to comply.

The Matrix of Change functions as a four step process. It provides a systematic means to judge those business practices that matter most. It highlights interactions among these practices and possible transition difficulties from one set of practices to another. It encourages various stakeholders to provide feedback on proposed changes. And, it uses process interactions to provide guidelines on the pace, sequence, feasibility, and location of change. These procedures were used successfully to analyze the reengineering process at a large medical products company (Austin), which we call "MacroMed." Steps from their implementation experience are presented to illustrate this process.

In the early 1970s, MacroMed, a producer of medical products, had enjoyed close to a 100% market share for "Betaplex," sterile adhesive compound mass-produced in its New Jersey facility. Between 1989 and 1991, however, the market share for Betaplex fell nine percentage points to about 48%, the fastest rate of decline in the previous 16 years. [1] Competition in the form of private label and new Japanese products were proving more cost effective and responsive to consumer demand (Austin). Senior management at MacroMed became increasingly alarmed.

To make matters worse, rising materials costs exerted upward cost pressure on Betaplex, resulting in an 18% price hike over the same period. Although Betaplex enjoyed excellent brand name recognition and a modest quality premium, the accelerating loss of market share was a spur for action.

MacroMed faced critical problems in their need for greater flexibility and modern manufacturing methods. They produced five varieties of Betaplex but had not invested in new equipment for years. Setup times for changeovers averaged almost 90 minutes and certain designated equipment could not switch product types at all. When certain products experienced low demand and others moved briskly, facilities utilization became very poor. MacroMed's union contract also enforced rigid and narrowly defined job categories, contributing to a lack of flexibility.

In response, senior management decided to design a new generation of manufacturing equipment and to stop using the relatively inflexible equipment available on the open market. They understood, too, that simply changing the technology without also rethinking their work organization, market strategy, supplier relations, and other aspects of their business would not lead to success. Accordingly, they wrote an explicit vision statement that outlined new policies and procedures in each of these areas. In realizing process interdependence, they were already ahead of many other firms.

Unfortunately, however, their early experience with the new system was not good. Despite a considerable investment in new capital and explicit calls for new approaches to work, productivity did not significantly improve and by some measures actually worsened. Clearly, the new equipment was not being used to its potential, moreover, there was some grumbling about poor management and leadership.

In an effort to coax more efficiency out of the equipment, MacroMed's managers put significant effort into formal modeling of operational details including equipment changeover times, capacity requirements and optimal queuing strategies. Factory visits, however, revealed that the core problem had more to do with an intrinsically difficult organizational transition than suboptimal machine scheduling or the actions of particular individuals. Despite instructions to the contrary, workers continued to use new equipment much as they had used the old, thus wasting its flexibility. Although piece-rate incentives had been eliminated, workers let large work-in-process and finished goods inventories build up rather than allow higher downtime. Their mental models still led them to follow the outdated heuristic that productivity would be maximized by keeping the machines running at maximum capacity with minimal changeovers. Similarly, line managers were reluctant to cede real authority to the operators. While they spoke of teamwork, empowering the workforce, and maintaining open and trusting communications, some managers suggested privately that operators did not really understand what was happening and therefore could not be trusted with real authority. There were also mismatches in the skill sets of some operators, who lacked any desire to assume decision-making responsibility, just as there were mismatches in contracts with suppliers and numerous other aspects of the work.

These complex interactions became apparent with the benefit of hindsight, but most were not explicitly considered in advance. Furthermore, it was unclear how to correct the problems given the significant investments that had already been made and the loss of forward momentum these difficulties were causing.

We developed the Matrix of Change to help organize and sort through these issues. The Matrix process has evolved since its inception as a research project originating in the Leaders for Manufacturing program and Center for Coordination Science at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Its development has therefore involved academic researchers, senior managers, and operators from the shop floor.

The Matrix of Change system consists of three matrices and a set of stakeholder evaluations. The matrices represent (1) the current collection of organizational practices, (2) the desired collection, and (3) a transitional state that bridges these two. The stakeholder evaluations provide an opportunity for persons within the firm to state the importance of these processes to their job activities. Matrix construction then proceeds in four steps.

Step 1 - Identify Critical Processes

Managers should first list their existing goals, business practices, and ways of creating value for consumers. Current practices are then broken into constituent processes suggesting how they are accomplished. A process is "a structured, measured set of activities designed to produce a specified output ... a specific ordering of work activities across time and place, with a beginning, an end, and clearly identified inputs and outputs. (Davenport, p. 5)" A second list will describe new or target practices.

Identifying the most important processes can be quite difficult, but certain guidelines can help. A key to success is "starting with the end in mind," that is, identifying the purpose or business objective of change, whether it is organizational learning, market share, flexibility, customer satisfaction, or something else. Since MacroMed already enjoyed high quality and brand name recognition, senior manager settled on increased flexibility and decreased costs as their principal goals - improvements that would permit both lower retail prices and the pursuit of niche market margins.

Another guideline is to choose members of the redesign team both for their knowledge of functions essential to business objectives and their ability to secure support from these functions during subsequent phases. One organizational change effort, for example, sought to cut 90 days from a corporate supply chain (Sterman). The change effort involved only order fulfillment staff, yet close examination revealed that total cycle time consumed 75 days of manufacturing lead time, 85 days of customer acceptance lead time, and 22 days of order fulfillment time. If the design team had eliminated 100% of the order fulfillment time, it still would have fallen 76% short of goal.

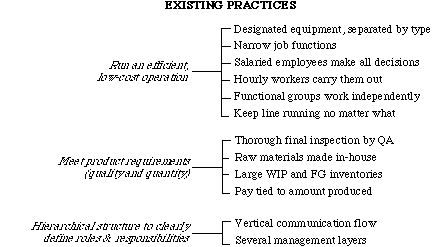

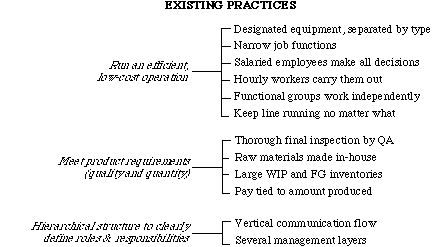

At MacroMed, senior managers assembled a SWAT team from a cross-section

of the workforce consisting of managers, design engineers, and

union workers across several different functions. The team began

by enumerating specific aspects of their existing hierarchical

production techniques, as well as forming their vision of a new

organization based on the perceived benefits of a flatter more

flexible production line. Then, from general statements of practice,

they defined subtasks or constituent practices (see Figures 1a

and 1b for an example).

Figure 1b: Break target practices into constituent parts.

The steps of any process can be broken down farther and farther, if this is helpful. The existing practice of "designated equipment," for example, can be further broken out to "sterilizing," "manufacturing," and "packaging." To keep explanations simple in this article, we will stop at two levels. Processes can also be grouped into categories by function (e.g., marketing, human resources, and manufacturing) [2] as well as by strategic initiative (e.g. elimination of non-value-adding costs and speed). MacroMed preferred the second classification, as Figure 1 illustrates.

Regardless of the level of detail analyzed, it is rare that all important practices can be identified in advance; enumerating a set of practices at the outset should be seen as a way to open the door to identifying new practices as the change progresses, not has obviating the need for subsequent adjustments.

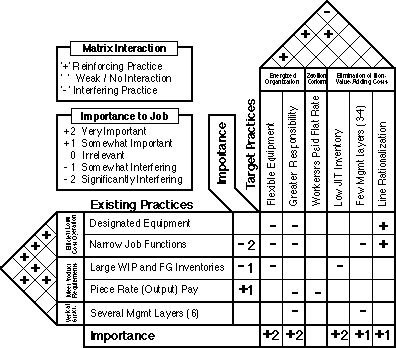

Step 2 - Identify System Interactions

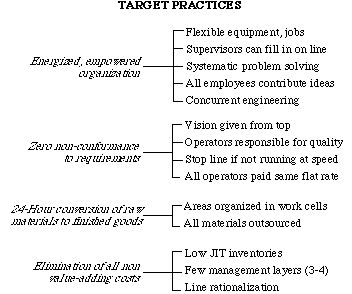

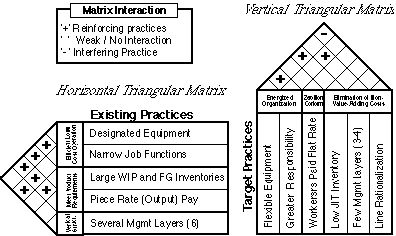

After describing existing practices, the team creates the horizontal triangular matrix to identify complementary and competing practices as illustrated in Figure 2. Complementary processes reinforce one another whereas competing processes work at cross-purposes. Doing more of one complement increases returns to the other. Narrow job functions in the existing system, for example, made tasks easy to specify and increased MacroMed's ability to offer piece-rate pay tied to hourly output. These practices were reinforcing. On the other hand, doing less of a competing practice increases returns to the other. A flatter managerial hierarchy, for example, would shift some strategic decisions to workers; this, in turn, would decrease MacroMed's ability to offer piece-rate pay tied to hourly output. These practices are interfering. Most existing frameworks do not capture interdependencies or process interference (Davenport and Short; Harrison and Loch) while interference matrices makes these interactions explicit.

A grid connects each process in an interference matrix, and at

the junction of each grid plus signs (+) designate complementary

and minus signs (-) competing processes. Thus since "designated

equipment" complements "narrow job functions"

the intersection of their grid is assigned a plus. The presence

of a plus sign does not indicate that an interaction is "good,"

only that it is reinforcing. In the absence of evidence to support

either reinforcement or interference, the space at the junction

is left blank. The horizontal matrix for a subset of MacroMed's

existing practices appears on the left half of Figure 2. [3] An analogous

process develops a vertical triangular matrix for target practices.

In the existing matrix, no competing practices were identified; this suggests that the system coheres as a stable unit. In contrast, the target triangular matrix has at least two competing practices. "Line rationalization," which relies on centralized optimization and infrequent adjustments, works in opposition to flexible equipment, which encourages local control and decisionmaking.

The plus or minus values for each cell can be derived in a number of ways. Often, once the practices are classified, the values become self-evident. In other cases, formal models and theory provide guidance. Theories of ownership, for example, suggest that decentralizing data management can boost quality levels in systems users control themselves (Alstyne, Brynjolfsson and Madnick) and operations management models suggest task processing in parallel adds more value when inputs have higher variance (Harrison & Loch, 1995). In some cases, empirical data will suggest the existence of complementarities or substitution effects, and formal statistical analysis can identify clusters of practices which tend to co-exist. [4] Surveying key personnel is also an effective way to gain insight into both perceived and real interactions. MacroMed used each of these approaches.

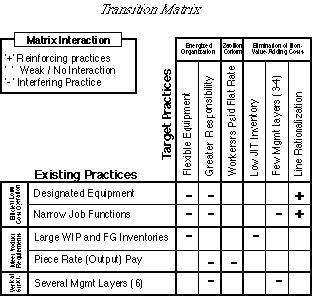

Step 3 - Identify Transition Interactions

Next, the team constructs the Transition Matrix - a square matrix combining the horizontal and vertical matrices which helps determine the degree of difficulty in shifting from existing to target practices. The advantage of the transition matrix is that it shows the interactions involved in moving from existing practices to a clean slate. Simply starting with a clean slate tells a team nothing about the difficulty of a transition (Harrison and Loch) while using a "blank sheet of paper" for design can implicitly assumes a "blank check" is available to cover implementation costs (Davenport and Stoddard).

A subset of the transition matrix used at MacroMed (Figure 3)

illustrates important interactions between existing and target

practices, a large majority of which are opposing. Narrow job

functions interfere with equipment flexibility and multiple layers

of management interfere with greater responsibility.

Certain practices complement one another. Line rationalization complements the use of designated equipment by reducing uncertainty around scheduling. Similarly, line rationalization complements narrow job functions.

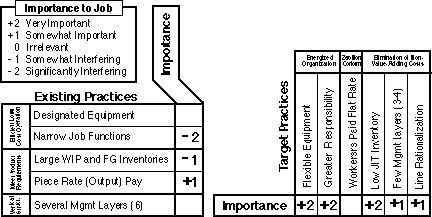

Next, the team needs to determine where various stakeholders stand

with respect to retaining current practices and implementing target

practices. Just as listening to the "Voice of the Customer"

is essential to building a better product, listening to the "Voice

of the Stakeholder" is essential to building a better process.

At MacroMed, several different groups were given the opportunity

to indicate how important each process was to their job performance.

Each surveyed employee used a simple five point Likert scale anchored

at zero. A value of "+2" means that a practice is

extremely important and a value of "+1" that a practice

is important but not essential, while a value of "-2"

indicates a strong desire to change or reject business as usual.

A value of "0," which can be omitted, represents indifference.

Figure 4 shows a brief completed example.

The respondent in this case feels strongly that, among existing practices, narrow job functions should be discontinued (-2), inventory levels should not be as large (-1), and piece-rate pay is somewhat important (+1). Blanks indicate zero values or no strong preference with respect to maintaining or eliminating these practices. [5] Regarding target practices, the respondent feels positively about most practices and indifferent about one.

Although these examples use a relative Likert scale, several variations are possible. As shown, they measure internal business value from the perspective of a single stakeholder. A "Balanced Scorecard" might also consider other stakeholders and perspectives, including financial indicators, customer preferences, and innovation requirements (Kaplan and Norton). Thus the axis for flexible equipment might be evaluated from the additional perspectives of improving customer product offerings and of reducing financial costs. If multiple indicators are required, multiple columns can be added. Ideally, a given metric will have quantifiable units such as accounting profits or the number of product configurations offered to the customer. If multiple measures are used, comparisons across practices must use the same units such as dollars or soft dollar estimates.

Combining Figures 2 through 4 creates the Matrix of Change (see

Figure 5).

A count of cross-connections is one measure of coupling strength or interdependence within blocks. Within the existing practices, "designated equipment," "narrow job functions," and "piece-rate pay" each have three connections with other practices. "Large WIP" has two and "several management layers" only one. In this sense, management layers are the least tightly coupled practices within this block. In contrast, the target state for this example has only small blocks which are independent and easily separable. [7] The large block of existing practices that involve "designated equipment" in Figure 5 will illustrate several principles discussed next.

Interpreting and Using the Matrix: Implications for Change Management

The Matrix of Change is a useful tool for addressing the following types questions:

Feasibility: Do the set of practices representing the goal state constitute a coherent and stable system? Is our current set of practices coherent and stable? Is the transition likely to be difficult?

Sequence of Execution: Where should change begin? How does the sequence of change affect success? Are there reasonable stopping points?

Location: Are we better off instituting the new system in a greenfield site or can we reorganize the existing location at a reasonable cost?

Pace and Nature of Change: Should the change be slow or fast? Incremental or radical? Which groups of practices, if any, must be changed at the same time?

Stakeholder Evaluations: Have we considered the insights from all stakeholders? Have we overlooked any important practices or interactions? What are the greatest sources of value?

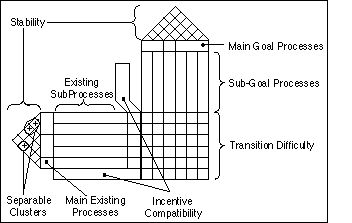

Each major area in the Matrix of Change serves various roles and

addresses different aspects of these five issues. Taken together,

they offer useful guidelines on where, when, and how fast to implement

change. Figure 6 points out the general purpose of the various

features.

Interpreting the information captured in the Matrix of Change motivates the principles which follow.

Feasibility: Coherence and Stability

The sign, strength, and density of interactions are important for determining process coherence and stability. A system of processes with numerous reinforcing relationships is coherent and therefore inherently stable, whereas one with numerous competing relationships is inherently unstable. The current system is quite stable at MacroMed; it appears to have no competing relationships. This is hardly surprising since the current system has been in place for decades, and practices have co-evolved. Fine-tuning a traditional approach over a period of years tends to eliminate conflicting practices.

The desired state in Figure 5 is also stable but has a single competing relationship. [8] This implies that it may require more effort to keep the parts working together. The business may also need to evolve new, non-competing processes or to propose alternatives that are at least neutral. If a proposed state has too many negative relationships, the project will be unstable and must be reevaluated. If a target state has few relationships, whether reinforcing or interfering, it will be neither likely to collapse nor tightly bound together. Thus, the tighter coupling of the existing system indicates that it is more inherently stable than the target system. Tight or loose coupling also predicts the level of coordination necessary to effect change. Loosely coupled practices require less coordination.

Critically, the transitional state for MacroMed is dominated by interfering relationships indicating a high degree of instability. This offers a fundamental explanation for the difficulty found in business process reengineering: when faced with new practices that conflict with current operations, well-intentioned local managers seeking to optimize their piece of the system will consciously or unconsciously undermine change by pushing the system back toward its initially stable state. From a local perspective, each manager's resistance appears sensible and even efficient, but from a global perspective structural change becomes almost impossible.

Sequence of Execution: Where to Start and When to Stop

The most easily eliminated practices are those that oppose other existing practices. While it can be tempting to do this, it can also be dangerous in that it may render the remaining system even more entrenched and difficult to change. Since stable systems generally have few opposing practices, another alternative is to start removing practices that have no inherent effect on other practices. On the goal side, the easiest new practices to implement are those that complement existing ways of doing business. This can be used to build a bridge from one system to the next, particularly where a practice has numerous complements in the new state. It should be avoided, however, if new practices strengthen old habits in ways that make dismantling the old regime even harder.

Practices that support a large number of other practices must be handled with great care. Such "linchpin" practices can be inserted to help lock several new practices in place or they can be removed to unlock several old practices. At MacroMed, the use of designated equipment acts as a linchpin practice; it has multiple dense complements, as Figure 5 illustrates.

Designated equipment - inflexible, high volume machinery - is one linchpin practice that facilitates narrow job functions and pay schedules that are tied to the amounts produced. Removing inflexible equipment helps with the simultaneous removal of the entire block. In the ideal case, completely independent blocks may be identified but in this case, the block's components have less impact on the number of management layers which might be changed separately.

Therefore, as long as the old designated equipment remains in place, it will be more difficult to expand job responsibilities, lower inventory levels, and remove piece-rate pay. For similar reasons, introducing new technology is often used intentionally as a catalyst to facilitate change management. Installing new equipment can signal an irreversible commitment to a new way of doing business, and can initiate a cascade of complementary changes in work practices as workers are forced to adapt. At MacroMed, one manager described the dramatic unveiling of the new technology:

"In phase 2, we took down the walls that had surrounded the new equipment, and assembled the new machines right on the manufacturing floor in their final location. The workers saw the new technology growing right around them. Because of this, people knew it was real and didn't want to be left out of it."

Although the new technology helped achieve buy-in from the workforce, it was not enough to overcome the ingrained routines of the factory without a lot of additional change management. Ironically, the very flexibility of the new technologies made it too easy to continue with the comfortable old routines. When flexible technology meets an inflexible workforce, often the machines, not the people, are forced to adapt. [9]

The larger the blocks of reinforcing processes, the more difficult they are to change. The hardest changes involve the installation of new practices that oppose the greatest number of existing practices. In fact, large new blocks may be impossible to install before the opposing practices are removed. One strategy is to dismantle these competing practices beforehand. Another alternative is to lay a foundation of complementary new practices before making the attempted change. Having support in place helps keep employees from reverting to old habits.

The presence of large blocks also suggests that change should stop only after a block has been completely removed. Reducing the pressure to change when an interlocking block is only partially dislodged can allow old practices to roll back into place, thus undoing work and wasting resources.

Location: Greenfield and Brownfield Sites

Since the density of interfering relationships in the transition matrix indicates how disruptive proposed changes will be, increasing interference indicates a greater need for isolation. Sometimes a fledgling change project needs to be shielded from bad habits. Natural tendencies toward local optimization will push the system towards an initially stable state as long as opposing practices remain. More disruptive changes make existing or brownfield sites less attractive. In fact, greenfield sites are much more popular for introducing new systems, even (or perhaps especially) when they require abandoning years of organizational learning.

Greenfield issues relate not just to location but also to attitudes. Radical change is "frame-breaking" in the sense that it requires changes in mental and mechanical (Tushman, Newman and Romanelli). Mental models involve (1) goals and values, (2) system boundaries, (3) causal structure, and (4) relevant time horizons (Sterman). A transition matrix with more densely interfering relationships can therefore indicate a greater need for changing mental models. For particularly radical or frame-breaking change, an outside change agent may be essential to helping people see processes differently. Managers may also need to be replaced because they are too closely tied to former ways of doing business. Also, if a group is left particularly worse off by change - in influence, responsibilities, etc. - it is often best to address this issue early because members will tend to reassert their former roles (Milgrom and Roberts; Rousseau). [10]

Pace and Nature of Change: Fast or Slow, Incremental or Radical

For purposes of implementation planning, it is worth distinguishing between the pace (gradual or rapid) and the nature (incremental or radical) of the change to be made (Gallivan, Hofman and Orlikowski). Occasionally, radical change may best be spread over several episodic steps (Gallivan, Hofman and Orlikowski) especially if resources are locked in place and initial conditions resist change (Barua, Lee and Whinston). A single step discontinuity may prove too disruptive, too expensive, or too confusing. And yet, as the European proverb suggests, there are other occasions when change is an all-or-nothing proposition. A halfway solution may lead to wasted resources, organizational exposure, or even failure.

Three factors help to determine an appropriate pace: task interdependence, organizational receptiveness to change, and external pressure. The first, task interdependence, concerns how modular and how serial the essential steps are (Leonard-Barton), that is the divisibility of organizational processes. Segmenting tasks into blocks reduces the scope of change and the coordination problem that must be managed at any given instant. The pace of change within blocks must be rapid; the pace of change between blocks may be slow. Thus the speed of removing parallel components of an interdependent block may be more important than the serial speed of the whole change process. At MacroMed, the existing block of practices associated with designated equipment in Figure 5 are interdependent whereas the target block associated with low JIT inventory is independent. The transition matrix, by showing interference, also suggests how radical a change must be. In other situations, incremental change is indicated if the transition matrix exhibits little interference. The role of the analysis, of course, is to help determine which situation applies before going down the wrong path.

The culture of an organization helps to indicate the second factor, its receptiveness to change. In a large chemical products company, the IS group was used to experimentation and risk taking, a situation that greatly facilitated an episodic approach (Gallivan et al., 1994). A big advantage of a supportive culture and episodic change is that it permits phased adaptation to unfamiliar practices. Particularly if change needs to migrate through several parts of an organization, episodic change can promote experimentation and learning so late adopters can access the know-how and know-why of the early adopters (Leonard-Barton; Orlikowski & Hofman) without repeating their mistakes. Experimentation, however, is unlikely if the culture punishes failed experiments. At MacroMed, the culture was not receptive initially to the kind of change that managers sought to undertake, but this cloud of resistance had a silver lining:

The fact that the first effort took place in one of [MacroMed]'s oldest unionized plants made the challenges surrounding the change-effort all the more great; however, that also made the success all the more marketable in [MacroMed]'s other locations.

External pressure is the third factor. Low pressure provides slack time for adaptation, but as an arbiter of pace, the environment may preclude the option of episodic change, for example, if the organization faces a crisis. With extreme external pressure, concern for survival and the absence of slack resources may force the pace to be rapid. This, in turn, interacts with the culture of an organization. If there is a history of opposition to change or a pattern of unsustained or regressive change, then transition times should be minimized. As Gallivan, Hofman & Orlikowski (1994, p.336) note "Under these conditions, managers' intentions for rapid implementation would seem appropriate given that the opportunity to change anything later may be lost as enthusiasm wanes, skepticism grows, resistance accumulates, resources are reallocated, and champions are reassigned."

Stakeholder Evaluations: Strategic Coherence and Value Added

Stakeholder evaluations make preferences and expectations explicit. Evaluations help anticipate responses to change by providing data on sources of support for, indifference to, or hostility toward proposed changes. If employees give an existing practice low marks, they are likely to support a change. Conversely, if they do not support a change they will likely give an existing practice high marks. They may require new incentives to support new proposals.

Whereas the transition matrix indicates the degree of process interference and the need to break mental models, the evaluations measure the alignment of incentives. Negative values in the target ratings section indicate a need to either cooperate and better align incentives, to increase pace and avoid drawing out resistance, or to isolate factions whose interests oppose the change initiative.

High variance among stakeholder evaluations indicate different priorities and a fragmented strategic vision. If evaluations were uniform across employee populations, then stakeholders within the company would jointly focus on tackling the most important issues first. With different priorities, however, stakeholders will tend to work at cross-purposes during implementation. When these differences occur, organizations may wish to establish a more uniform strategic vision early in the change process.

Stakeholder evaluations open a window onto organizational receptiveness to change. In their case study of a large chemical company, Gallivan, Hofman and Orlikowski found that a tradition of open experimentation, a willingness to invest in technology without immediate payoff, and a philosophy of empowerment and learning all created norms that facilitated change. These factors influence the willingness of stakeholders to cope with, to participate in, and to accept responsibility for change.

The very act of decentralizing decision-making - asking workers for their values and then taking them seriously - can have a positive effect on the change process by giving employees a sense of ownership and responsibility. At MacroMed, the workers attitudes changed noticeably:

They played the role of 'final customer.' They decided where engineering and operations resources should be focused. They also made supplier decisions and traveled together to supplier sites. ...There is true measurable value in soliciting and developing ownership at the worker level, at the early stages of change.

Determining the Net Value Added

Once key differences in stakeholder evaluations have been addressed,

a simple mechanism gives an indication of which changes will ultimately

add the most value. The formula Target Value - Existing Value

gives an approximation of the net value to be gained by changing

practices. This assumes that all units are the same and that practices

with no counterpart are paired with a value of zero. Thus "line

rationalization," a target practice with no existing counterpart,

has a net value of 1 - 0 = 1. A means of visualizing the net value

added is to sort practices in a "Tornado Plot." This

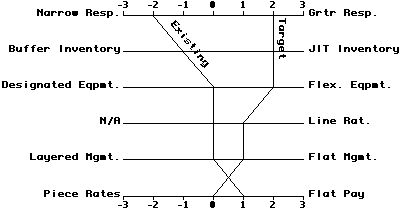

diagram, illustrated in Figure 7, connects importance ratings

across categories so that the spread is monotonically decreasing.

Net values can also be negative, as in the case of a stakeholder

who feels he or she can earn more through piece-rates than through

flat pay.

Net value added provides a useful complement to the Matrix of Change, but it can be misleading if used in isolation. Principles of net value suggest which changes are important, but principles of coherence suggest which sequence to adopt. Many consulting projects aim to get the big payoff items first (Sterman, Repenning and Kofman), but this can be counterproductive, and the Matrix shows why. A "greedy" algorithm, which sorts changes based solely on the best value, will miss the possible cost reductions brought about by setting up complements (Croson). The net values in Figure 7, for example, appear to suggest first giving workers more responsibility then reducing inventories and so on, proceeding through the list in a sequence that gains the next best value at each step. This process might stop before implementing the last step which appears to add negative value. The matrices in Figure 5, however, show that some practices are reinforcing. For instance, at MacroMed, narrowly defined job responsibilities complement the use of designated equipment, so the least cost path involves changing them together rather than two steps apart. Although net value methods suggest changing to just-in-time inventories before moving to flexible equipment, this could even be counterproductive. It could lead to stockouts or increased worker frustration and resistance.

Although cutting layers of management may not create as much value as improving the product offering through flexible equipment, Figure 5 shows how multiple layers of management complement narrow job descriptions. It may not be possible to have workers assume greater responsibility when they face oversight at multiple levels. In this case, moving to flatter management constitutes a "stepping stone" - a practice that smooths the adoption of other practices (Nolan and Croson).

The sequence of changing practices affects not only how soon any given payoff may be realized but also the cost and feasibility of changing other practices. Thus there are "alpha" and "beta" benefits to the order of adoption (Croson; Nolan and Croson; Rosenberg). Alpha benefits represent immediate returns while beta benefits represent subsequent gains achieved through "setting up complementarities in the adoption of future [practices]" (Croson, p. 32) Beta benefits also accrue from "learning by doing other things." In the process of learning to operate with fewer layers of management, an organization may also learn the process of distributing responsibility.

The greatest benefit from the Matrix of Change may be that it forces management to make explicit the practices and interactions that are implicit in the old, new, and transition systems. Recognizing and defining the nature of the problem can be 80% of the battle, but without a tool for clearly sorting out interactions among principles, much of change management is relegated to intuition and politics. Once the elements of the Matrix of Change have been identified, the most effective strategy may become self-evident.

The Problem of Prediction in Complex Systems

Of course, despite data provided by the Matrix, companies consist of myriad unarticulated rules, procedures, technologies, and cultural mores that can never be completely catalogued, or even recognized. The most detailed list will inevitably overlook certain unstated assumptions inherent in any system of work. The result of any elicitation or mapping process is "a set of causal attributions, initial hypotheses about the structure of the system which must then be tested" (Sterman, p. 321). The Matrix of Change helps managers identify important assumptions implicit in their work organization, but they must keep in mind that key components of any system may remain unmodeled, allowing unexpected barriers to surface in the midst of the change process.

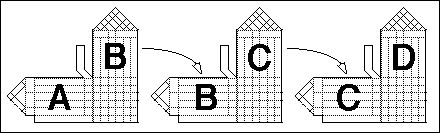

The Matrix of Change can offer two forms of assistance, if not

complete assurance, in dealing with complex systems. The first

is that the Matrix design process can be revisited as often as

necessary. Each design phase can represent a temporal time slice,

or window onto current and possible outcomes as Figure 8 suggests.

Matrix chaining can highlight important stepping stones or phases that can be skipped entirely. A transition from craft production, to mass production, to modern manufacturing, for example, might omit the intermediate step or use it as a bridge, depending on the ease of the associated transitions. Refining the Matrix across several levels of detail or across time slices can lead to the development of organizational meta-principles, such as the observation that a pair of process dependencies frequently recur. This pair might then be integrated or replaced wholesale. Having identified certain dependencies and interactions, systematic process behaviors might be amenable to software simulation to aid in prediction. Reflecting actual events, a feedback model of total quality management practices at Analog Devices found significant quality and productivity improvements did not translate into higher financial performance (Sterman, Repenning and Kofman). The software offered controlled and repeatable simulations that helped identify a confluence of interacting business practices and environmental factors causing the trouble. The matrix can provide important inputs to such a system.

A second form of assistance is help in reshaping mental models. At MacroMed, workers held the unarticulated goal of running the machines at all times to increase productivity. This led them to resist product line change-overs and inadvertently to defeat the value of flexible equipment. As this belief surfaced, MacroMed managers devised compatible incentives and achieved a more coherent work system. To the extent that the Matrix can help shift mental models even part way from implicit to explicit parameters, it can improve chances for success. It may never be possible to "manage the magic" of a perfectly functioning system, but managers need simple ways to initiate debate on critical changes. The Matrix helps initiate that inquiry, it helps identify multiple interactions, and it uncovers at least some of the hidden assumptions.

At MacroMed, we administered a set of questionnaires based on the Matrix of Change to multiple groups within the company. This included managers, engineers, and hourly employees in both the company at large and in a special pilot project designed to test the proposed changes.

Having MacroMed employees fill in the Matrix proved to be highly informative. For instance, management within the pilot group saw positive reinforcement between flexible machinery and line rationalization, an interaction that is inconsistent with the literature. Line rationalization, a top-down optimization process, tends to reduce the scope for on-the-spot decision-making and reconfiguration of flexible machinery.

Worker matrix data also showed a certain degree of ambivalence regarding management. Rather than viewing it as a partnership, workers considered that having supervisors work the line would discourage workers from contributing new ideas or expanding their roles. At the same time, a surprisingly large subset of workers expressed no desire to become "empowered" with responsibility for programming the equipment. They preferred their traditional roles, which required little on-the-job thinking, allowing them to daydream and chat with co-workers while doing the parts of the job requiring physical work.

Several assumptions about the transition surfaced during data gathering, but other assumptions did not surface until the new system was implemented. For instance, although piece-rate pay was eliminated and an explicit goal of reducing WIP inventory was established, most workers continued to behave as if the paramount performance indicator was eliminating machine downtime. As a result, they avoided changeovers and kept the flexible machines running on the same product line almost as much as they had with designated equipment. Although this no longer increased the profitability of the factory or their individual pay, this and many other heuristics were too ingrained to be easily overturned.

Overall, the high density of interfering relationships in the transition matrix highlighted the need for a greenfield approach. Since a completely new site was too expensive, MacroMed chose a modified greenfield implementation. One portion of the factory was physically isolated with a temporary new wall, then workers and managers were carefully selected for the "SWAT" team. Implementation proceeded in two phases. During the first phase, the SWAT team debugged the most difficult technologies and procedures. They reorganized the line and reduced obsolete finished goods inventories to zero. Once the process was established, the SWAT team helped disseminate flexible manufacturing practices throughout the remainder of the factory and to other plants. They served as trainers and troubleshooters for the second phase of implementation. As one MacroMed manager put it:

"All members of the SWAT team, both union and salaried, shared equally in the responsibility... Because they were given as much responsibility as the salaried employees, the union workers on the team cared greatly about the outcome of the project and they were a positive influence on bringing the other union workers in the plant over to the new way of doing things."

Paralleling the episodic introduction of radical change (Gallivan, Hofman and Orlikowski), this modified greenfield approach greatly simplified MacroMed's transition. Workers reported that job security was critical, indicating that a sudden transition from a piece-rate incentive scheme to different incentives based on meeting new goals - such as new ideas contributed, lower inventory, and accepting greater responsibility - could be too disruptive.

MacroMed chose to offer flat-rate compensation initially while workers adjusted to their new roles and began to more fully understand the risks while management gained a better understanding of behaviors they wished to promote. Wage guarantees thus lowered worker resistance to the new changes. As the head manager of the SWAT team observed, "Equipment issues are easy; the people issues are the tough part." Other factors that eased the transition included the use of contract employees and hand-selected union workers who were receptive to change.

Applying the Matrix of Change, MacroMed also discovered conflicts in different employees' set-up procedures. This revealed a way to reorganize process changeovers and resulted in a 67% reduction in setup times as well as a dramatic reduction in variability. Other successes included a fourfold increase in throughput and waste costs cut by 65%. Purely through attrition and early retirement, the number of line employees was reduced by 33% while staff employees were reduced by almost 40%. MacroMed stopped its decline in market share. Moreover, flexibility and response time improved to the point where products could move from concept to store shelf in just 99 days, an impossible time frame under the previous practices. The success was such that management ordered the windows painted black in the portion of the factory devoted to the new approach to prevent visitors and competitors from observing their organizational and technical innovations.

The findings from our study of MacroMed and similar companies underscore that successful change often depends on leveraging complementary practices and on redesigning contingent business processes. Managing and coordinating increasingly complex systems, however, requires increasingly sophisticated tools.

Flexibility in manufacturing relies not only on powerful new information technologies, as is commonly emphasized, but also on a mutually reinforcing set of practices in the areas of cross-training, incentives, inventory policy, decision-making structure, and open door communications among others, which function as a coherent and stable system. Not only is it difficult to isolate a single practice and graft it onto another work organization to achieve the same effect, but also many subtle interactions often go unnoticed until it is too late. Juxtaposed against this argument, the high failure rate of business process reengineering seems less mysterious: without proper tools, most business process reengineering efforts are unlikely to have accounted for the complexities, the finely balanced complements, and the time delays of a stable and coherent system.

By systematizing change management, the Matrix of Change can help. It selects those practices most likely to contribute to business goals. It detects complementary and interfering practices, and presents an overview of an interlocking organizational system. It helps capture the alignment of incentives, showing which practices are the greatest sources of value to stakeholders. Then after identifying interactions, it suggests guidelines for judging a proposed system's feasibility and coherence, its sequence of execution, and its relative pace of change. By focusing on the difficulty of a transition, the Matrix of Change also suggests how disruptive or radical the change is likely to be and thus provides an index of the need for a greenfield location. From this overview, management can learn where it has the greatest leverage in implementing change and which changes are most important.

Each element of the Matrix of Change proceeds from fairly intuitive concepts of reinforcement and interference. MacroMed used these steps to develop a deeper understanding both of how its existing practices cooperated with one another and of how practices they wished to introduce meshed with what they had done in the past. Since the list of practices can be disaggregated to an arbitrary level, the Matrix can be applied to the whole organizational structure, the department, and the shop floor.

It is also possible to proceed in the other direction and consider aggregation through the entire value chain, including suppliers, in-bound logistics, out-bound logistics, buyers, and even competitors (Porter and Millar; Venkatraman). From this perspective, the Matrix can also be used as a measure of environmental fit, answering questions about how well current or proposed practices work with or against the environment. If environmental factors oppose one another in a triangular matrix, they indicate instabilities that might uncover new opportunities. Unstable environments require more flexible - possibly networked - organizations, with a premium on innovation. If environmental factors reinforce one another, they indicate stable systems that are unlikely to change or that might change all at once, a change in regulation, for example, can create a cascade of shocks to the system. A more stable environment requires a more structured organization with a premium on efficiency. Commodity markets, for example, tend toward stable, cost-based competition (Alstyne; Snow, Miles and Coleman).

Since the change process is likely to unfold over a period of time, the Matrix should be revisited as necessary to gauge progress. New relationships can be captured as managers develop a deeper understanding of their situation. Managing change without regard to context or interconnections misses what is most important. The true value of the Matrix is to optimize steps not just in isolation but as parts of an integrated system with a more cohesive fit.

In adopting change, businesses typically look for cost savings, a first order effect. Savings then free up resources that can be substituted into other areas - a second order effect that should also influence business decisions. Third order effects, however, are those which are most often missed. These represent whole new structures or systems for organizing work (Malone, Yates and Benjamin). Flexible machinery adds little value in environments accustomed to rigidly hierarchical procedures, large inventories, and little autonomy. But in conjunction with shorter production runs and just-in-time deliveries, its effects upon competitors can be devastating. Financial analysis alone frequently does not uncover third order effects because it can overlook complements in strategies and structures, as well as unanticipated interference from incompatible practices. The Matrix of Change can make it easier to identify complementary structures and it gives change agents an intuitively appealing tool for managing them.

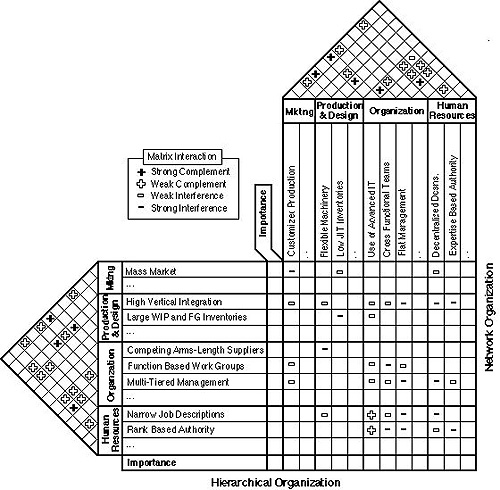

Reinforcement and interference themes recur frequently. One important

business process reengineering version is the transition from

a hierarchical to a network organization. Hierarchies tend to

be vertically integrated, mass-production organizations that seek

scale economies through long production runs of commodity products

and that reduce risk by owning assets they use (Malone, Yates

and Benjamin; Williamson). Network organizations, on the other

hand, tend to be partnerships which exploit strategic opportunities

by rapidly and flexibly adjusting their outputs to niche markets,

seeking scope economies through complementary, possibly intangible,

assets, and that reduce risk through equity arrangements, repeated

cooperation, and trust (Alstyne; Powell). Members exercise joint

control over assets rather than taking direction from an executive

body. Hierarchical and network practices may be internally consistent

but juxtaposed against one another typically they compete. Milgrom

and Roberts discuss the differences between "lean manufacturing"

and "mass production." In a survey of attributes,

Alstyne also provides a direct comparison of hierarchies and networks.

Table 1 lists elements from these two systems and illustrates

the strong differences between their methods for organizing work.

Internally, these systems appear to be coherent. Long mass production runs accompany large inventories just as highly customized products accompany flexible machinery. It is unlikely, however, that mixing elements of these independently coherent systems will result in another coherent system (Milgrom and Roberts). In fact, placing several of the organizational attributes from Table 1 into the matrix framework (Figure 9) illustrates the difficulty of a potential business process reengineering effort. In aggregate terms, the endpoints are stable and cohesive but the transition from a hierarchical to a network organization appears to be generally unstable. Given the number of competing practices in the transition region, it is not surprising that, for this type of change, reengineering projects that implement only a handful of features have difficulty reaching their goals.

Although advanced information technology is typically associated

with modern manufacturing more than traditional mass production,

it is interesting to note how adding it can complement practices

in both systems. If IT is used for coordination and decision support,

it can complement cross-functional teams and flatter management,

as in the vertical interactions matrix. By providing everyone

with the same data, it can also undermine expertise-based authority.

On the other hand, if IT is used for monitoring and automation,

it can complement narrow job descriptions and rank-based authority,

as in the transition matrix. The dual character of IT has been

observed in literature (Attewell and Rule). If an organizational

feature has multiple attributes, it may be helpful to split it

into discrete practices, such as disaggregating IT into monitoring,

decision support, and automation.

The authors thank James Champy, Kevin Crowston, Michael Gallivan, Deborah Hofman, Mary Pinder, Jack Rockart, Robert Sombert, the referees, and numerous anonymous individuals at "MacroMed," the case site discussed in the paper for helpful comments and insights. They also acknowledge the Leaders for Manufacturing Program, the Center for Coordination Science, and the Industrial Performance Center at MIT for generous financial support.

Alstyne, Marshall van. "The State of Network Organization: A Survey in Three Frameworks." Journal of Organizational Computing (forthcoming) (1996).

Alstyne, Marshall van, Erik Brynjolfsson, and Stuart Madnick. "Why Not One Big Database? Principles for Data Ownership." Decision Support Systems 15.4 (1995): 267-284.

Attewell, P., and J. Rule. "Computing and Organizations: What We Know and What We Don't Know." Communications of the ACM 27 (1984): 1184-1192.

Austin, Amy B. "Management and Scheduling Aspects of Increasing Flexibility in Manufacturing." . Masters Thesis: MIT Sloan School, 1993.

Barua, Anitesh, S. H. Sophie Lee, and Andrew B. Whinston. "The Calculus of Reengineering." : Department of Management Science, UT Austin, 1995.

Bashein, Barbara J., M. Lynne Markus, and Patricia Riley. "Preconditions for BPR Success." Information Systems Management 11.2 (1994): 7-13.

Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Lorin Hitt. "Paradox Lost? Firm-level Evidence of the Returns to Information Systems Spending." Management Science (1996).

Champy, James. Reengineering Management. New York: Harper Business, 1995.

Croson, David. "Towards a Set of Information-Economy Management Principles." : Wharton School of Management, 1995. Ed. (unfinished work).

Crowston, K., & Malone, T. (1988). Information Technology and Work Organization. In M. Helander (Ed.), Handbook of Human-Computer Interaction, (pp. 1051-1069): Elsevier.

Davenport, Thomas. Process Innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1993.

Davenport, Thomas, and Donna Stoddard. "Reengineering: Business Change of Mythic Proportions?" MIS Quarterly 18 (1994): 121-127.

Davenport, Thomas H., and James E. Short. "The New Industrial Engineering: Information Technology and Business Process Redesign." Sloan Management Review 31.4 (1990): 11-27.

Dudley, L., and P. Lasserre. "Information as a Substitute for Inventories." European Economic Review 31 (1989): 1-21.

Gallivan, Michael, J. Debrah Hofman, and Wanda Orlikowski. Implementing Radical Change: Gradual versus Rapid Pace. Vancouver, British Columbia: Association for Computing Machinery, 1994. 325-339.

Hammer, Michael. "Reengineering Work: Don't Automate, Obliterate." Harvard Business Review July-August (1990): 104-112.

Hammer, Michael, and James Champy. Reengineering the Corporation. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

Harrison, J. Michael, and Christopher H. Loch. "Operations Management and Reengineering." : Stanford Business School, 1995

Hauser, J., and D. Clausing. "The House of Quality." Harvard Business Review (1988): 63-73.

Henderson, Rebecca, and Kim Clark. "Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms." Administrative Science Quarterly 35 (1990): 9-30.

Holmstrom, B., and P. Milgrom. "The Firm as an Incentive System." American Economic Review 84.4 (1994): 972-991.

Jaikumar, R. "Postindustrial Manufacturing." Harvard Business Review (1986): 69-76.

Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. "The Balanced Scorecard -- Measures that Drive Performance." Harvard Business Review July-February (1992): 71-79.

Krafcik, J., and J. MacDuffie. Explaining HIgh-Performance Manufacturing: The International Automotive Assembly Plant Study. Acapulco, Mexico, 1989.

Leonard-Barton, D. "Implementation as Mutual Adaptation of Technology and Organization." Research Policy 17 (1988): 251-267.

Leonard-Barton, D. "Implementation Characteristics of Organizational Innovations: Limits and Opportunities for Management Strategies." Communications Research 15 (1988): 603-631.

Malone, Thomas W., Joanne Yates, and Robert I. Benjamin. "Electronic Markets and Electronic Hierarchies." Communications of the ACM 30.6 (1987): 484-497.

Milgrom, P. , and J. Roberts. "Communication and Inventories as Substitutes in Organizing Production." Scandanavian Journal of Economics 90.3 (1988): 275-289.

Milgrom, Paul, and John Roberts. "Complementarities and Fit: Strategy, Structure, and Organizational Change in Manufacturing." : Stanford Department of Economics, 1993.

Milgrom, P., and J. Roberts. "The Economics of Modern Manufacturing: Technology, Strategy, and Organization." American Economic Review 80.3 (1990): 511-528.

Nolan, Richard, and David Croson. Creative Destruction. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Orlikowski, W., & Hofman, D. (1996). An Improvisational Model of Change Management: The Case of Groupware Technologies. Sloan Management Review, Winter((forthcoming)).

Osterman, Paul. "Impact of IT on Jobs and Skills." The Corporation of the 1990s -- Information Technology and Organizational Transformation. Ed. Michael Scott Morton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991. 220-243.

Parthasarthy, Raghavan, and S. Prakash Sethi. "Relating Strategy and Structure to Flexible Automation: A Test of Fit and Performance Implications." Strategic Managment Journal 14 (1993): 529-549.

Porter, Michael, and Victor Millar. "How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage." Harvard Business Review (1985): 149-160.

Powell, Walter W. "Neither Market Nor Hierarchy: Network Forms of Organization." Research in Organizational Behavior 12 (1990): 295-336.

Rockart, John F., and James E. Short. "The Networked Organization and the Management of Interdependence." The Corporations of the 1990s. Ed. Michael Scott Morton, 1991. 189-216.

Rosenberg, Nathan. Inside the Black Box: Technology and Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Rousseau. "Managing the Change to an Automated Office: Lessons from Five Case Studies." Office: Technology and People 4 (1989).

Snow, Charles C., Raymond E. Miles, and Henry J. Coleman. "Managing 21st Century Network Organizations." Organizational Dynamics 20.3 (1992): 5-20.

Sterman, John. "Learning In and About Complex Systems." System Dynamics Review 10.3 (1994): 291-330.

Sterman, John, Nelson Repenning, and Fred Kofman. "Unanticipated Side Effects of Successful Quality Programs: Exploring a Paradox of Organizational Improvement." Management Science (forthcoming) (1996).

Suarez, Fernando F., Michael A. Cusumano, and Charles H. Fine. "An Empirical Study of Flexible Manufacturing." Sloan Management Review 37.1 (1995): 25-32.

Tushman, M., W. Newman, and E. Romanelli. "Convergence and Upheaval: Managing the Unsteady Pace of Organizational Evolution." Readings in the Management of Innovation. Ed. M. Tushman and W. Moore: Harper Business, 1988. 705-717. Ed. not read.

Venkatraman, N. "IT-Enabled Business Transformation: From Automation to Business Scope Redefinition." Sloan Management Review (1994): 73-87.

Williamson, Oliver E. Markets and Hierarchies. New York: North-Holland, 1975.

2 An illustration of this grouping is illustrated in the Appendix on transitioning between organizational structures.

3 Only pairwise interactions are identified. In principle, more complex interactions may be important; for instance, two practices may be complements only in the presence of a third practice. Typically, framing the question in terms of a reference set of practices will resolve such potential ambiguities without resorting to a matrix with more dimensions.

4 Specification of such models must be done with some care since the clustering of variables will depend on the source of heterogeneity in the environment that gives rise to sample variation (Holmstrom and Milgrom).

5 "Importance" can be usefully interpreted as "Benefit - Cost" of the practice in isolation. This interpretation is revisited in the section on determining net value added.

6 See Apppendix A for a larger and more complete matrix, illustrating the transition from a hierarchical to a network organization.

7 For a large system of interconnections, a graph spanning algorithm can identify independent blocks of practices as well as connection counts within blocks.

8 An early analysis of the complete set of fifteen new practices discovered several other competing relationships. Most were associated with the practice of “line rationalization” which seemed appealing when proposed in isolation (who could be opposed to “rationalization"?), but which conflicted with the principles of worker empowerment and flexibility embodied in many of the other practices.

9 Firms adopting the popular SAP software package report that it is inflexible in how it handles many basic business functions. Typically, this forces them to change their business practices to conform to the software's requirements. Some customers view this as a feature, not a bug, because it compels recalcitrant managers to discard their old practices.

10 In principle, if the new system really does create more value, then it should be possible to compensate the losers so that everyone is better off. In practice, it may be hard to determine which grievances are legitimate, so some claims will need to go uncompensated. Nonetheless, if a majority of stakeholders appear to be worse off under a new system, this is a warning sign that the change is merely re-allocating benefits and not creating much new value.